The meat analog market in the 1970s was in need of a facelift. At the time, meat analogs were divided into two types of products: soy based and wheat based. The problem was that while meat analog products looked like meat and tended to be healthy, their taste and texture were so unconvincing that eating soy dogs and soy burgers was often likened to chewing on tasteless cardboard. It was a niche market dedicated to “hard-core” vegetarians.

Meanwhile, a young Israeli food technologist, Michael Shemer, was methodically trying to invent “edible” meat analogs. He focused his efforts on three essential attributes: taste, texture, and nutritional value. He experimented for years with wheat and soy proteins and in the early 1980s had a breakthrough when he combined the two vegetable proteins. He quickly evolved his technology into a line of meat analog products and found a home for them at Kibbutz Lohamei HaGeta’ot. Production began in 1985 under the name of Tivall, later to become part of the Nestlé Corp.

The new products met the growing demand from consumers who wanted nutritional, yet tasty meat substitutes suitable to their dynamic, on-the-run lifestyles. Today, Tivall is a world leader in the industry and renowned for its rapid product development and award winning, innovative products. Many of us may know, or may even be, a food technologist whose fate has followed a similar path. For Shemer, however, this was only the beginning of a life-long quest for a more structured approach to inventing new-to-the-world food technologies—a method he later adopted, called Systematic Inventive Thinking®.

Where Ideas Come From

Traditionally, there exist three sources for new product ideas: (1) surveying competitors, (2) identifying needs through market research, and (3) developing new technologies. Surveying competitors, often known as the “safe path,” cannot result in unique or differentiating products, as they largely offer consumers more of the same, just under a different brand name. Furthermore, research shows that these “me-too” products have an 80% chance of failure, which is the same as (or slightly higher than) “new-to-the-market” products. Catering to identified market needs, although crucial for keeping a company competitive in the market, rarely results in true innovations. Research conducted by Goldenberg and Mazursky (1999) validates that customers are a poor source of quality information when it comes to innovation, since most people find it difficult to imagine things that do not yet exist. Although consumers do have latent needs, they are not fully aware of, it is difficult for them to state them explicitly. Moreover, polling a consumer base that is equally available to all players in the market makes it difficult to identify unique needs and create exclusive products that the competition does not yet have in development. The authors concluded that “There is a clear need for an approach that can lead to exclusive discoveries that can take the marketplace by surprise. Such innovative ideas must be captured before the market submits strong signals to its needs, rendering market research methods (for eliciting ideas) less effective.”

Developing a new technology platform can be a strong source leading to proprietary innovations, but it thereby poses a twofold problem: First, it is not a process by which a company can plan its pipeline. When exactly a new technology will be ready for market is a fickle and unreliable phenomenon. Second, creating a completely new technology is often the more-expensive and high-risk option. The only source leading to true innovation—new technology development—must become a process that is more efficient.

New Technology Development

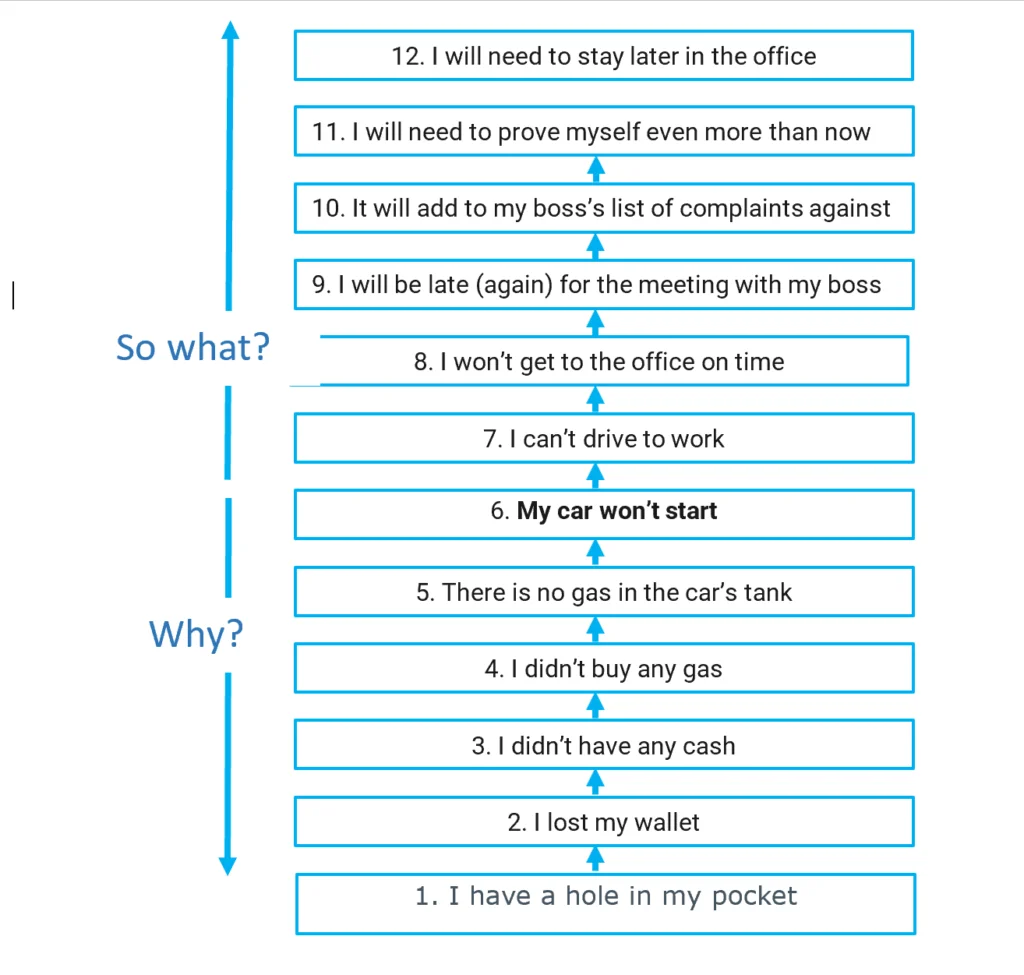

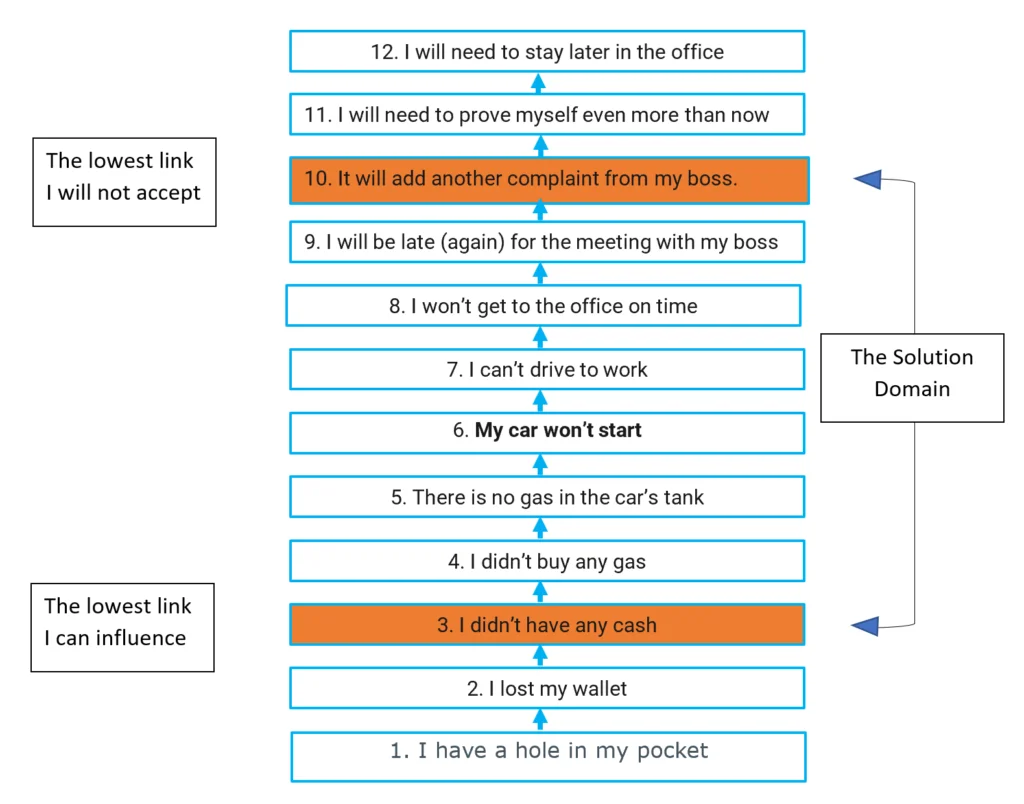

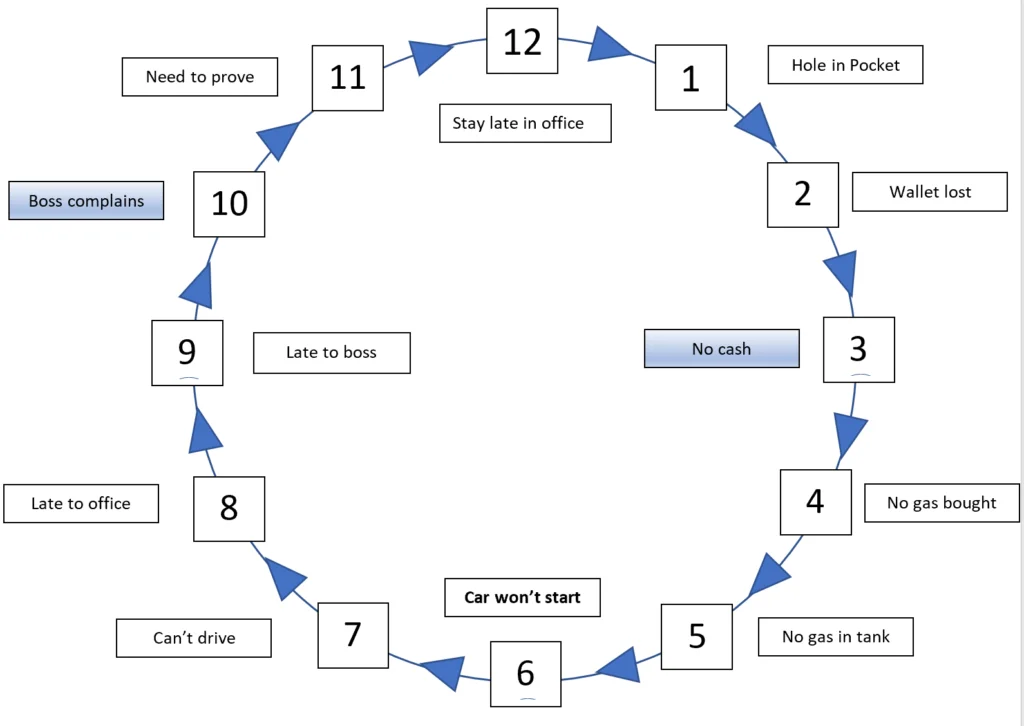

To many, creativity is synonymous with free thinking. It is believed that if only there were no constraints, people could think of the wild, breakthrough ideas for their industry. Yet, studies by Goldenberg et al. (1999) showed that constrained-thinking processes provided superior results to ideas generated by humans thinking without constraints. This idea superiority was apparent for both the creativity and originality evaluations of the ideas. The aura of free thinking for generating innovation nevertheless endures. This is because many constraints truly are stifling for creativity. Thus, it is not enough to say that constraints enhance creativity, rather the proper constraints—those that promote creativity—need to be identified.

One of these “creativity-facilitating constraints” is the Closed World principle. This principle posits that the only resources for innovating are those that already exist in the product’s immediate environment (Horowitz and Maimon, 1999). These include the essential elements in the product, including its physical components as well as its variables like color or size. The immediate environment of the product is also inventoried for its components and variables. These elements—and only these elements—lead to finding new ideas and solutions. No new types of resources or technologies are allowed to enter into the idea-generation process. Unknowingly, Shemer utilized the Closed World principle when inventing his product. As opposed to his unsuccessful attempts at using other plant-based materials, the secret to his success was manipulating elements within the two leading meat analog bases—soy and wheat proteins, resources already existing in the Closed World. One of the Closed World’s main benefits is that it relies solely on a company’s existing resources and knowledge base, providing a “leg-up” so that it needn’t start from scratch and can more readily assess the feasibility of the solution.

One of these “creativity-facilitating constraints” is the Closed World principle. This principle posits that the only resources for innovating are those that already exist in the product’s immediate environment (Horowitz and Maimon, 1999). These include the essential elements in the product, including its physical components as well as its variables like color or size. The immediate environment of the product is also inventoried for its components and variables. These elements—and only these elements—lead to finding new ideas and solutions. No new types of resources or technologies are allowed to enter into the idea-generation process. Unknowingly, Shemer utilized the Closed World principle when inventing his product. As opposed to his unsuccessful attempts at using other plant-based materials, the secret to his success was manipulating elements within the two leading meat analog bases—soy and wheat proteins, resources already existing in the Closed World. One of the Closed World’s main benefits is that it relies solely on a company’s existing resources and knowledge base, providing a “leg-up” so that it needn’t start from scratch and can more readily assess the feasibility of the solution.

Shemer, as well as many other developers in parallel industries, realized in hindsight that he had been inventing by applying the Closed World principle all along. Had he realized what he was doing earlier, his development process would have cut down years of research, instead of happening by “accident,” during one of several dozen experiments. Once aware of the Closed World principle and the benefits it provides, Shemer learned a system to more proactively apply constraints to expedite product development processes.

Vegetable Dough Example

A prime example of this is Shemer’s leadership role in the development of Tivall’s latest award-winning product, a revolutionary vegetable dough (Figure 1). As Vice President of Strategic Innovation and R&D, he was assigned the task of innovating an existing Tivall product line: vegetable-filled pastries. Tivall’s core competency—its Closed World—is innovative uses of vegetable materials. With that in mind, Shemer’s rephrasing of his task was already half of the solution: To identify new ways to use vegetable elements in the pastries to generate an innovative food technology platform.

Utilizing his food technology knowledge, he was able to find a way to replace more than 85% of the flour in the product. The technology used to integrate the vegetables into the dough allowed for a completely new line of products consisting of puff pastry dough, yeast raised dough, and short dough, each of which can be made of different types of vegetables, including sweet potatoes, spinach, corn, and cauliflower. More benefits of this proprietary dough became apparent with the realization that it could also be marketed as a separate product for home cooking and baking. The vegetable dough was launched in 2005 and met with instant success. It won an award in the Savory Frozen Foods category at the 2006 Sial International Exhibition of Food Industry.

An Innovation Algorithm

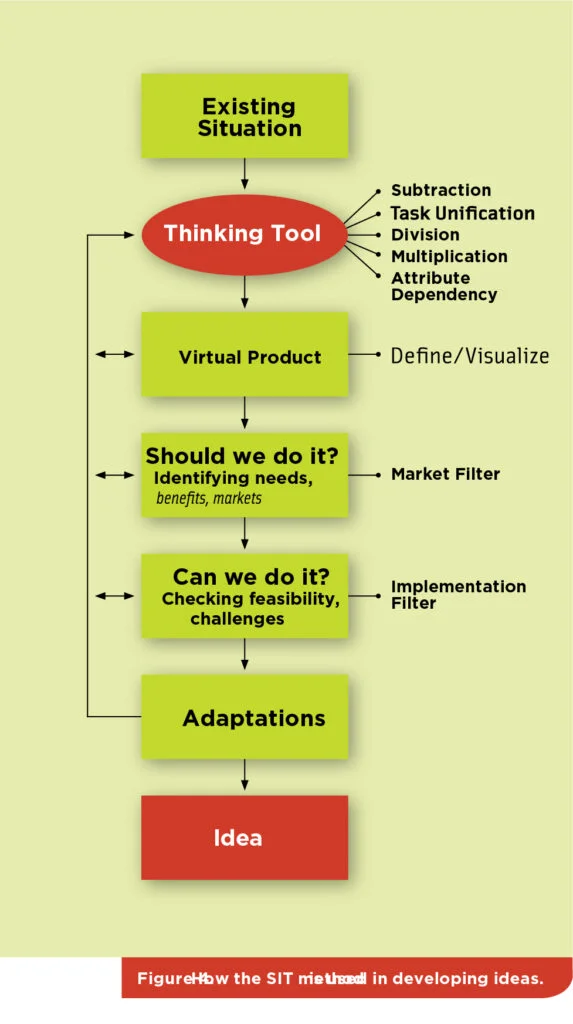

While the Closed World principle identifies the resources that we are allowed to use (and those we are not), it does not dictate enough how to use these resources. This, another variety of constraint, needed to be formulated to guide the developer in a more systematic manner through the thinking process. The solution was found in a body of research begun by Genrich Altschuller, a naval engineer from the former Soviet Union, who studied thousands of patents and found that creative solutions share common patterns. Based on his research results, he developed a method that he called Theory of Inventive Problem Solving (TRIZ). His students later evolved the method into what is today called Systematic Inventive Thinking and expanded Altschuller’s pattern recognition into the field of product development. It is evident that inventors unknowingly follow patterns when coming up with product ideas. In essence, they impose on themselves thinking constraints that result in innovative outputs. A novice inventor would expect there to be dozens, even hundreds, of patterns that lead to inventions. This makes SIT’s findings that more than 70% of successful new products can be categorized according to only five patterns even more surprising. In contrast, fewer than 20% of unsuccessful product launches could be classified according to these same patterns (Goldenberg and Mazursky, 2002). The following are the five patterns in this approach:

• Subtraction. This pattern instructs the inventor to look at the Closed World and, as opposed to the conventional approach to new product development, subtract an essential element rather than add one. This constraint is unintuitive in two senses: first, we are not adding or improving something to create a new offering in the market; second, the subtracted element cannot be one that was originally detrimental (e.g., fat), but one that was thought to be essential, with no logical reason for being subtracted.

Examples of this pattern are largely seen in the “instant” product category, such as soups or cakes from which the liquid or eggs was subtracted. Although understandable today, it is easy to imagine the resistance to the concept of removing the water (essentially, the soup) from the soup when the idea was first proposed.

• Multiplication. While it is clear how subtracting something essential from a resource-base would be a strong constraint, with the Multiplication pattern it is less obvious. This pattern allows the technologist to add elements that were previously not available. Nevertheless, what is allowed to be added is highly constrained. This pattern is about adding one or more copies of an existing component in the product or system, and then modifying the copy so that it is different according to one of its original component parameters.

Pizza Hut’s Stuffed Crust Pizza is a good example. When looking to innovate pizzas, the most common path is to simply add a different type of topping or to change the organoleptic properties of one of the primary ingredients (e.g., the dough or sauce). However, the stuffed crust was a true innovation and example of Multiplication, since it added more of an existing component (the cheese), but changed its location on the diameter of the pizza (placing it inside the crust). The consumer benefit was readily apparent: the pizza eating experience now facilitated more cheese in every bite, especially toward the edge of the pie, where cheese is not typically sprinkled on top. Not surprisingly, when it was launched in 1995, it became one of Pizza Hut’s more successful products.

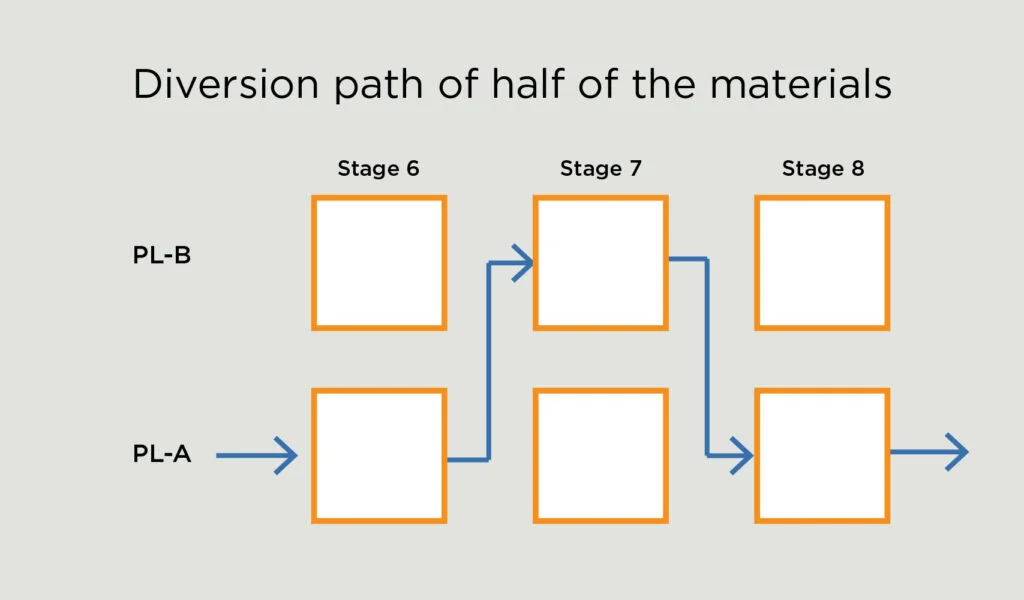

• Division. This pattern dictates that all product components remain and none are added, but several are reorganized in time or space. Thus, the product gestalt is broken, degrees of freedom are added to the thinking process, and the Closed World remains confined. This pattern is noticeable in a wide range of solutions for products suffering from short shelf life. Products such as Yakult and Actimel, including functional ingredients like probiotics, are healthy for consumption but have shelf life challenges because their potency deteriorates in a liquid medium.

The Swedish company BioGaia provided an innovative solution to lengthen the shelf life: separating (dividing) the probiotic culture from the yogurt. Its LifeTop straw supplies the consumer with Lactobacillus reuteri in each sip (or through a bolus during the first draft) through the straw instead of being mixed in with the yogurt. The straw allows yogurt producers to keep the probiotic ingredients dry, separate from the yogurt, until the actual time of consumption. The VIZcap™ (www.vizdrink.com) offers a similar solution in the vitamin-enhanced sport drink segment. The supplements are kept separated from the liquid by being stored in a sealed chamber inside the bottle cap. They are only added to the drink just prior to consumption, dropping into the liquid when the consumer twists the cap to open it.

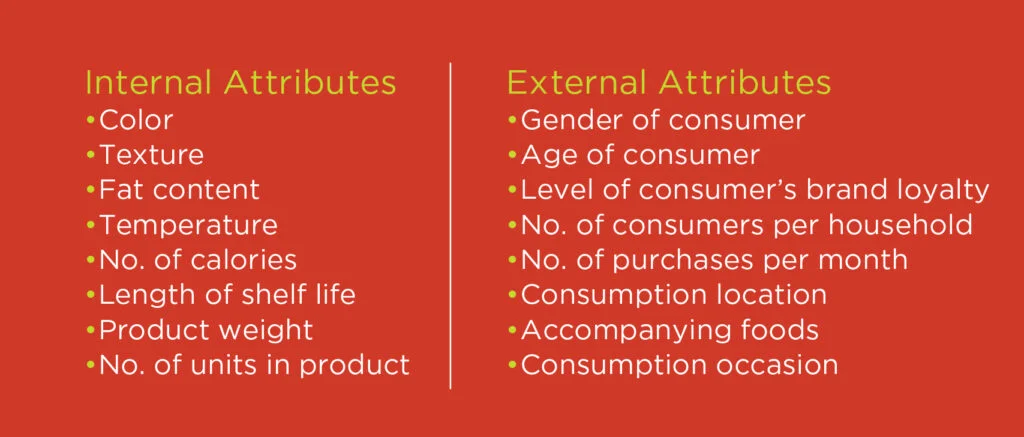

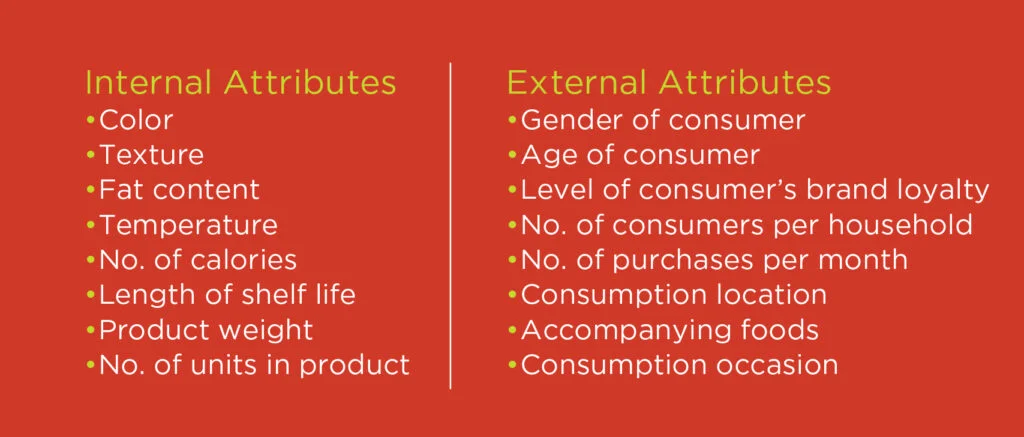

• Attribute Dependency. This pattern relates to the attributes or variables that exist in the Closed World of the product. It involves the creation of new relationships between the variables of a product or its immediate environment. Attributes of a product (Figure 2) can be internal, such as its texture, color, fat content, and temperature; or external, such as consumer attributes (e.g., gender, age) or consumption attributes (e.g., consumption location, eating occasion, accompanying foods).

When SIT Ltd. was invited to conduct a project with Nestlé Corp., the chosen topic was flavor solutions. Salad dressings were chosen as the Closed World starting point for generating ideas. The internal attributes were systematically paired with external attributes to identify interesting new relationships. When working with “texture” and “accompanying foods,” the developers posited that the product’s texture can be changed according to the food on which it is being used. A list of typical accompanying foods was hastily created (e.g., lettuce, tomatoes, sandwiches, chips, burgers, etc.) to make the process as systematic as possible.

An idea began to emerge as the developers imagined a thicker-textured dressing for sandwich usage. Marketing saw the emerging opportunity and suggested that it could be a spreadable dressing for sandwiches, similar in texture to mustard or ketchup. To that point, people had been observed pouring Nestlé’s existing Thousand Island dressing onto their sandwich bread to add flavor, trading sogginess for taste. The spreadable solution would solve this contradiction. As a result, Nestlé launched in Israel a line of sandwich spreads, including Thousand Island and Garlic flavors, positioned for sandwich consumption (Figure 3).

• Task Unification. In this pattern, an additional task is given to an existing resource. This tool helps to eliminate “functional fixedness,” in which each component is seen to perform only one task and additional tasks require the addition of more components. The essence of this pattern is to view all of a product’s existing components as potential resources that function in more than one role.

Unilever’s Cornetto was originally manufactured by an Italian ice cream manufacturer, Spica, who in 1959 was able to solve the problem of marketing frozen ice cream cones. Until then, it was difficult to market frozen ice cream cones because the ice cream caused the cone to dampen over time. Spica overcame the problem by inventing a process in which the inside of the waffle cone is coated with a mixture of oil, sugar, and chocolate, insulating it from the ice cream. Oil, sugar, and chocolate had always been available resources in the Closed World of ice cream but had their own tasks of promoting either texture or flavor. Utilizing these same components for the purpose of insulation was considered a breakthrough. Today, we can witness several examples of chocolate coating inside non-frozen cones to prevent ice cream leakage during consumption.

A Systematic Approach

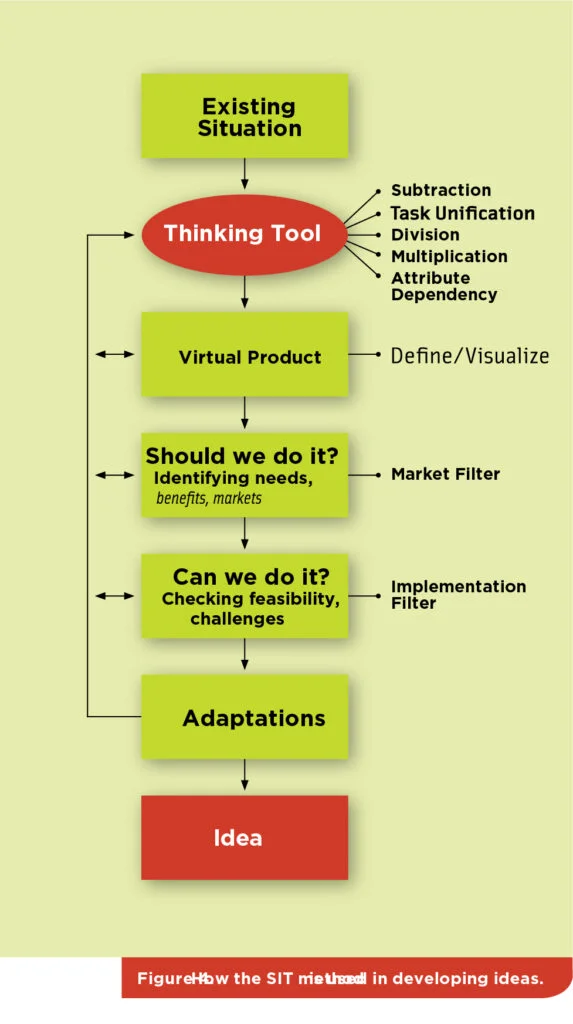

Combining the Closed World principle with the five patterns results in a much more structured approach, the SIT method (Figure 4). Let’s examine this approach through the process of vegetable dough invention:

First, the developers defined the Closed World of the product. They broke the product down to its fundamental components and identified available resources. These included the various types of vegetables used for the fillings, as well as dough ingredients such as flour and other grains, salt, sugar, vitamins, and packaging.

First, the developers defined the Closed World of the product. They broke the product down to its fundamental components and identified available resources. These included the various types of vegetables used for the fillings, as well as dough ingredients such as flour and other grains, salt, sugar, vitamins, and packaging.

Second, they applied the task unification tool. They systematically examined each component to see whether its function could be performed by the vegetables or some elements of them. Scoping out the list of components, they considered their options for manipulation. Seeing that the vegetables already dominated the inside of the pastry, they asked themselves whether the vegetables could also take over the outside.

Third, they defined the “virtual product.” The team envisioned creating pastry dough out of vegetables.

Fourth, they identified needs, benefits, and markets. The market value of such a product was clear—it could offer high nutritional value with low caloric value and almost no saturated fats. As for its innovative appeal, the developers felt that a product like that could be the basis of an entire platform of product lines.

Fifth, they checked feasibility and identified challenges. After the team unsuccessfully s subtracted all the flour, several adaptations led to a final product that had only 15% the normal amount of flour in it. The remaining 85% was replaced by vegetables by extracting the starches and other constituents of the vegetable and using them to replace the starches of the dough.

Of course, this thinking process does not replace market testing. It is at this stage that we look outside our company—to the market—for inputs. Thus, marketing research remains an integral part of the innovation process, but it simply moves to a later stage. Companies no longer need to depend on the market to raise ideas for them—there is a structured, internal process for that. The research is there to validate and “tweak” the ideas to make the technologies as marketable as possible.

A Recipe for Success

The SIT process leads developers to innovative technological concepts that can surprise and delight the market. But, because of the constraints, the process also relies heavily on the existing knowledge base of the company, as represented by its food technologists. In fact, this is the very reason that SIT ideas—and new technology ideas in general—lead to differentiated products in the market. Instead of depending on information streaming in from the market—a source available to everyone—the ideas arise as a product of the company’s unique intellectual property, proprietary knowledge, and current resources. Developing new technologies in an efficient, structured manner, leading to differentiated, innovative products on the market is what we’d call a recipe for success.

BY YONI STERN, ROBYN TARAGIN, AND SHAHAR LARRY

Originally published FOOD TECHNOLOGY 10.07

Some of these innovation challenges have to do with the process of ideation itself, while others with implementation, some are more relevant on an individual level, and others more on the organizational level. For this discussion, we can define one set of barriers that stop us from coming up with the right ideas (ideation / individual) and another set of challenges involved in the attempt to implement these ideas (implementation / organizational).

Some of these innovation challenges have to do with the process of ideation itself, while others with implementation, some are more relevant on an individual level, and others more on the organizational level. For this discussion, we can define one set of barriers that stop us from coming up with the right ideas (ideation / individual) and another set of challenges involved in the attempt to implement these ideas (implementation / organizational).

One of these “creativity-facilitating constraints” is the Closed World principle. This principle posits that the only resources for innovating are those that already exist in the product’s immediate environment (Horowitz and Maimon, 1999). These include the essential elements in the product, including its physical components as well as its variables like color or size. The immediate environment of the product is also inventoried for its components and variables. These elements—and only these elements—lead to finding new ideas and solutions. No new types of resources or technologies are allowed to enter into the idea-generation process. Unknowingly, Shemer utilized the Closed World principle when inventing his product. As opposed to his unsuccessful attempts at using other plant-based materials, the secret to his success was manipulating elements within the two leading meat analog bases—soy and wheat proteins, resources already existing in the Closed World. One of the Closed World’s main benefits is that it relies solely on a company’s existing resources and knowledge base, providing a “leg-up” so that it needn’t start from scratch and can more readily assess the feasibility of the solution.

One of these “creativity-facilitating constraints” is the Closed World principle. This principle posits that the only resources for innovating are those that already exist in the product’s immediate environment (Horowitz and Maimon, 1999). These include the essential elements in the product, including its physical components as well as its variables like color or size. The immediate environment of the product is also inventoried for its components and variables. These elements—and only these elements—lead to finding new ideas and solutions. No new types of resources or technologies are allowed to enter into the idea-generation process. Unknowingly, Shemer utilized the Closed World principle when inventing his product. As opposed to his unsuccessful attempts at using other plant-based materials, the secret to his success was manipulating elements within the two leading meat analog bases—soy and wheat proteins, resources already existing in the Closed World. One of the Closed World’s main benefits is that it relies solely on a company’s existing resources and knowledge base, providing a “leg-up” so that it needn’t start from scratch and can more readily assess the feasibility of the solution.

First, the developers defined the Closed World of the product. They broke the product down to its fundamental components and identified available resources. These included the various types of vegetables used for the fillings, as well as dough ingredients such as flour and other grains, salt, sugar, vitamins, and packaging.

First, the developers defined the Closed World of the product. They broke the product down to its fundamental components and identified available resources. These included the various types of vegetables used for the fillings, as well as dough ingredients such as flour and other grains, salt, sugar, vitamins, and packaging.