How Nudgers can be Nudged to Nudge

The work of the duo Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, further developed and popularized by Dan Ariely and others, has led to the growing popularity and use of Behavioral Economics in general, and the practice of “nudging” specifically, in advertising, marketing and communications. We refer to “nudging” here as the act of creating positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions to influence the behavior and decision-making of groups or individuals. A heated discussion has developed of late as to the validity of the idea that these small nudges can indeed move their targets to action, following what seem to be inconsistencies in the research and even some accusations of misrepresentation of data and results. Nevertheless, in this post we assume that, at least in some scenarios, it is useful to utilize so called nudges, and the task is finding the most effective way to perform them. [If you do not believe that “nudges” exist or can be useful, we recommend that you use your time to read other posts, ours or others’. If you do believe in nudges, this can be useful stuff for you].

In essence, we wish to nudge the nudgers to utilize a specific set of tools that can help them come up with effective ideas quickly and consistently. We will, therefore, focus here on HOW to create these prods.

This year I (Idit) reached the ripe age of 50. I’m not a big fan of counting my years, but my HMO does take age seriously, so they keep sending me notifications and requests to perform a set of examinations. I consistently ignored these well-intentioned messages (probably a topic for another post…) including repeated invitations for a mammograph, until, one day, a nurse called my mobile and declared: “I’ve scheduled a mammography for you, for next Thursday at 5pm. If you can’t make it, please send us a cancellation.” [What did I do?, you may ask]. I went 😊. The nudge nudged me into the desired action. Let us review a few additional examples, to point out some interesting patterns.

Many campaigns have been run across cultures to raise awareness to and combat drunken driving. How can nudges be enlisted for this purpose?

Aurora Bar, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, with the help of their ad agency (Ogilvy), came up with a set of creative solutions. A valet parking service was offered to clients, with a small twist: the driver in whose hands you were to deposit your car was visibly drunk. Customers were obviously reluctant to hand over their car keys to a drunkard, clearly unfit to drive anyone’s car. Some were even upset to the point of raising their voice and rebuking the driver for being unprofessional and irresponsible. At that point, angry customers were handed a note by the drunk valet parking attendant. The note read: “Do not let any drunk driver drive your car, even if the driver is you yourself”. [Watch the customers reactions here]:

https://www.adforum.com/creative-work/ad/player/34464465/drunk-valet/bar-aurora-e-boteco-ferraz

Another solution implemented in the bar was a first-of-its-kind karaoke breathalyzer. The karaoke system’s microphone was adapted to become an alcohol breathalyzer, so that when happy customers who had had their fill of alcohol took the stage and opened their mouth to sing, they were surprised to see, at the end of the song, their alcohol level displayed on the karaoke screen. The singers got the message, and so did their friends.

Brilliant solutions, aren’t they? Looking for commonalities between the two ideas, one can see that in both cases there is a “free-riding” element. Valet parking services were there anyway, they were just assigned an additional task – reminding the still-sober customer of the perils of drunken driving. The karaoke system was there anyway – it was just assigned the additional task of revealing the revelers’ blood alcohol level, both to them and to their friends.

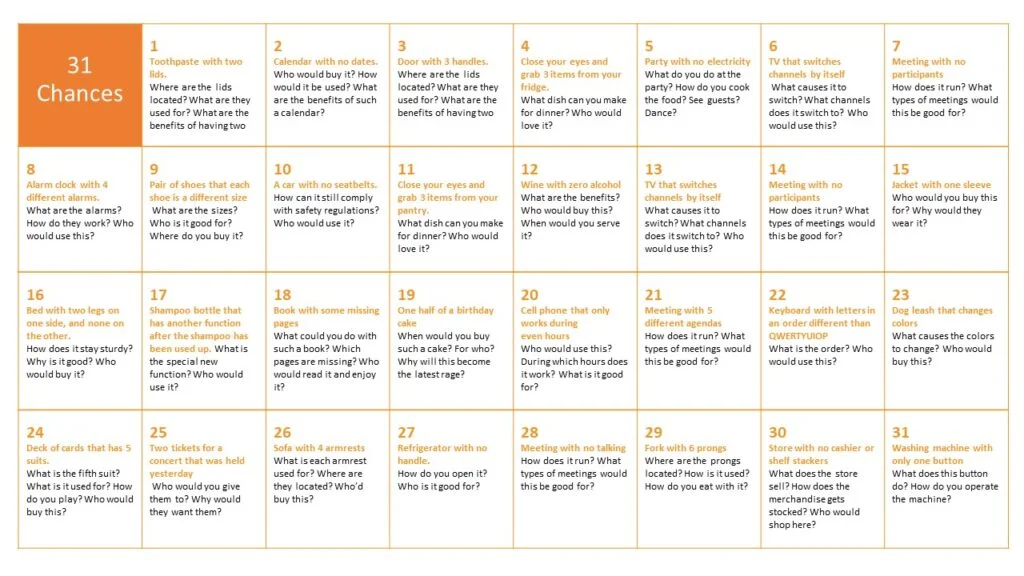

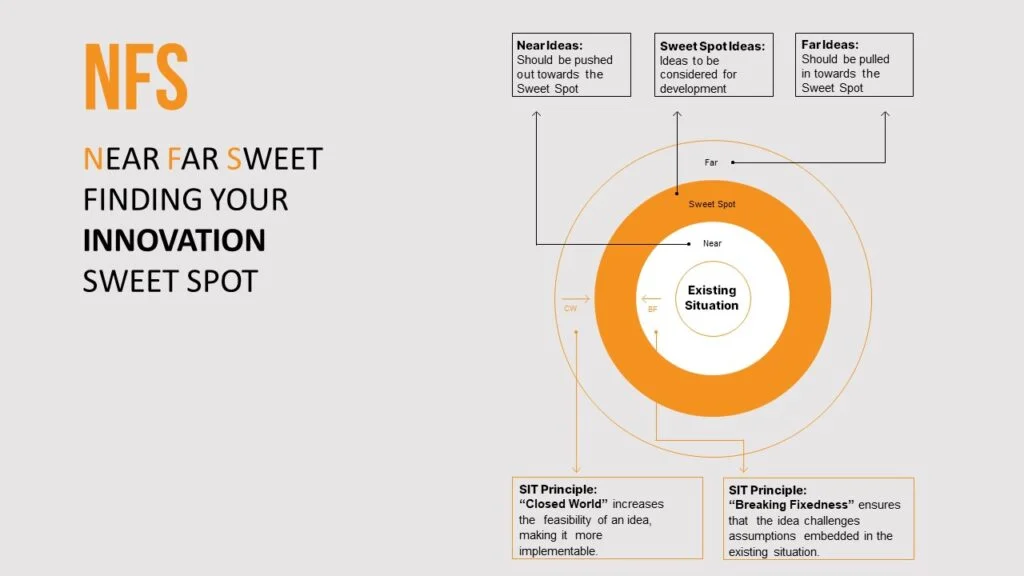

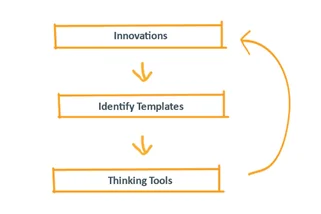

In SIT, we call this pattern of thinking, or thinking tool: Task Unification. But, before we delve into the specifics, a word about thinking tools in general. SIT’s thinking tools are defined by observing and analyzing thousands of inventions, detecting common patterns among them and converting them into tools that have been used in the past 26+ years in thousands of companies and organizations to invent products, solutions, services, strategies, and communication campaigns.

Task Unification (TU), in SIT, means assigning an additional task to an existing resource.

The Aurora Bar solutions are examples of applying Task Unification, since new and additional tasks were assigned respectively to the parking attendant and the microphone.

[You are welcome to try this yourself, continuing with the bar example. What elements does one typically find in a bar? Components that are there anyway? For example: stools, coasters, ceiling, toilets, music, food, smartphones, social media, speakers. Can you think of another nudge idea – assigning the task of reminding people not to drink and drive to one of the components mentioned above? Could you share this idea with us as a comment to this post? Or as a personal message to one of us?]

To introduce a second tool that leads efficiently to effective nudges, we will share an old example from a medium that is rapidly going out of fashion. We will then show how the very same logic is applied some 20+ years later using updated media, finally, we will ask our-and-yourselves what the 2022 version could look like.

The following was a brilliant and impactful campaign run by Amnesty International in Spain.

Note that the act of cutting out the coupon (yes, imagine that some of us old timers can remember the days when people actually cut out coupons and mailed or used them!) concretely demonstrates the result that your donation is meant to promote. You break the handcuffs, save the prisoner about to be hanged, etc.

Two elements stand out when you compare this add to a basic version in which the coupon would simply appear beside the text and visual:

- The reader is invited to perform a physical action;

- The reader receives a small immediate payoff for their action.

The results of these two features of this type of ad are:

- Engaging in physical action can increase engagement and long-term retention of a message. In addition to the everyday experience suggesting that this is the case, there is apparently a growing body of research on “Embodiment Theory” which proposes that knowledge is grounded in sensorimotor experiences. [If you are aware of relevant research, we would love to hear about it]

- When the viewer is hesitating as to their engagement with a message or willingness to act on it, we are assuming that a “nudge” can make the difference – the extra payoff in the action can be this nudge.

Let’s observe how this plays out in several additional examples.

The following “SocialSwipe” campaign, from 2014, uses a very similar idea to that used by Amnesty, but with a newer and more sophisticated medium: a billboard invites you to swipe your credit card on the billboard itself, with the double result of both transferring a donation to Misereor, and cutting a visual loaf of bread to feed a hungry child. [Watch 90 seconds here, of how it plays out]:

The following campaign was created by Publicis Brussels for Reporters without Borders, a non-profit organization which defends the freedom to be informed and to inform others no matter in which regime. Note the interesting combination of traditional print media with a cellular app, in which a phone, placed on top of the ad, hijacks three autocrats’ faces to pronounce an anti-dictatorial message “Because there are mouths that will never speak the truth.”

Two of these three autocrats we have been liberated from thankfully, but creepy to think that, 11 years after the campaign, [one of them is still with us, damaging the world with renewed toxic vigor]:

[Have you seen other examples of this type of Nudge-Activation lately? Can you share with us so that we can both enjoy and analyze them?]

How does one go about deliberately creating this kind of message-nudging?

When you wish to convey a message, through a medium, that will lead the viewer to perform a required action, we recommend using the Nudge-Activation tool. Use the medium to create an extra payoff that will nudge the viewer to perform an action which is either the required action itself or will serve as a bridging action and second nudge for the required action.

The direct version: In the SocialSwipe example the required action was swiping your card to donate. The extra payoff of this very action was seeing the bread being cut.

The double-nudge version: In the autocrat campaign the required action was donation to Reporters Without Borders, the extra payoff was seeing the dictators’ faces pronouncing anti-repression words, and this payoff, together with the physical action of triggering it, would hopefully nudge the viewer into performing the required action of donation.

[Try applying this tool, by following the simple procedure]:

Applying Nudge-Activation

- Define the required action – the action you would like the viewer to eventually perform.

- Possibly define a bridging action – a small action that can serve as a nudge towards performing the required action.

- Invent an extra payoff that the viewer will receive once they perform either the bridging action or the required action.

- Search your medium, your message or the environment of consumption of the message for resources that can help implement the extra payoff or perform the actions. Examples of components used in our examples are: the viewer’s phone, their credit card, the magazines paper, the billboard itself, a coupon, YouTube, social media. [Note that in this part you are using the Task Unification tool, described in the first part of this post]

- Combine your message with an invitation to act, presenting the extra payoff or hinting at it, using an existing resource.

Getting you into this article may have required some nudging – we tried our best in the accompanying post, but once you were in it, we did our best to engage you in thinking about our content in a practical way, maybe even asking yourself how you could go about using our tools. [Can you identify the myriad ways we attempted to nudge you towards our objective?] We tried to pepper the article with hints [[[]]] and will be happy to read what you thought about these efforts. Thanks.