Driving Organizational Innovation – Roles and Responsibilities Part 2

In Part 1 of this series, we shared a table detailing roles and responsibilities, with several caveats:

- Not all roles need to be defined in all organizations;

- Names of roles vary across organizations, as do the demarcations between territories and responsibilities;

- Role definitions can and should be dynamic, changing with the development of the innovation program or drive;

- Roles can start as part-time activities and develop into full-time, or they can start as FT and settle down into PT when processes flow more independently and require less external pushing and driving.

As roles and processes are being defined, organizations often ask themselves whether governance and responsibility over innovation should be centralized into a corporate entity dedicated exclusively to innovation or better be distributed throughout the organization. The table below assumes a hybrid approach: some of the functions are centralized (Sponsor, VP Innovation, SC, Coordinator), while others are expressly dispersed (coaches, managers, owners etc.). This structure is designed to make the most of both variants, each with its pros and cons.

Advantages of the centralized approach:

- More efficient in terms of budget and headcount, by avoiding the replication of efforts in numerous divisions or territories;

- Allows the creation of a dedicated team of high-caliber experts in innovation who can then share their knowledge and expertise throughout the organization;

- Facilitates quicker and easier access to top decision makers and purse-controllers;

- Makes it easier to align with company strategies and design innovation policies according to the big organizational picture;

- Some activities, such as incubation of startups, may require isolation from daily activities, which is easier to guarantee outside of the business units;

- Promotes cross-pollination, knowledge transfer and use of shared resources between diverse units, by becoming an innovation hub.

Advantages of the distributed approach:

- Innovation is perceived as an aspect of the “real business” as opposed to an impractical theoretical exercise of “the suits” in corporate;

- Goes in hand with the dictum of “Don’t do innovation, but rather innovate in what you do”, because innovation is happens where the organization’s core activity takes place;

- When business units need to pay for innovation activities (even if, as we recommend, they are sometimes subsidized by corporate) there is an immediate feedback loop, since they will agree to pay only for those activities that generate tangible value for them;

- The cycle – innovation-process->implementation->testing->adaptations->launch->innovation-process – is much quicker the closer one is to the field, which makes for a more adaptive and thus eventually more effective innovation process.

We therefore believe that a good mix of centralized and distributed roles can create an optimal structure. Below you can see the table as it appeared in Part 1, and following the table, some comments and a bit of a deeper dive into several of the roles that appear in it.

Some comments and tips about several of the roles:

- iSponsor, CEO/President. At the risk of stating the obvious: we have consistently seen a strong correlation between the level of involvement and commitment of the head of an organization and the traction of an innovation drive. Although the easy route, and the policy of choice for many a CEO is to remain at the declarative level, the effective approach is to prove to the sceptic internal public, tired of bombastic initiatives that dissipate within a few months, that this time around he or she really means it. Practically speaking this requires: a) allocating budgets (money where mouth), b) participating in innovation-related meetings and activities, and, the toughest and therefore rarest of innovation-promoting behaviors, c) demonstrate that s/he themselves can change their habits and modes of thinking as expressed in (some of) their actions.

- Steering (“Stirring”) Committee. The SC’s role is pretty obvious, we just wish to add that the adjective “stirring” is not a typo, but the expression of the idea that unlike many a SC, this one should engage both in giving directions and in rocking the boat so that other associates will be free to move and shake, challenging and changing existing structures. I wanted to write “easier said than done” but realized that this concept isn’t even easy to say, let alone do. Still, it is very much worth the effort of trying to instill this spirit in your SC which in turn will hopefully transmit it to the organization.

- Core Steering. Just because a SC, even of the “stirring” ilk, tends to be unwieldy, and you want to have the ability to move quickly (but try not to break things(:

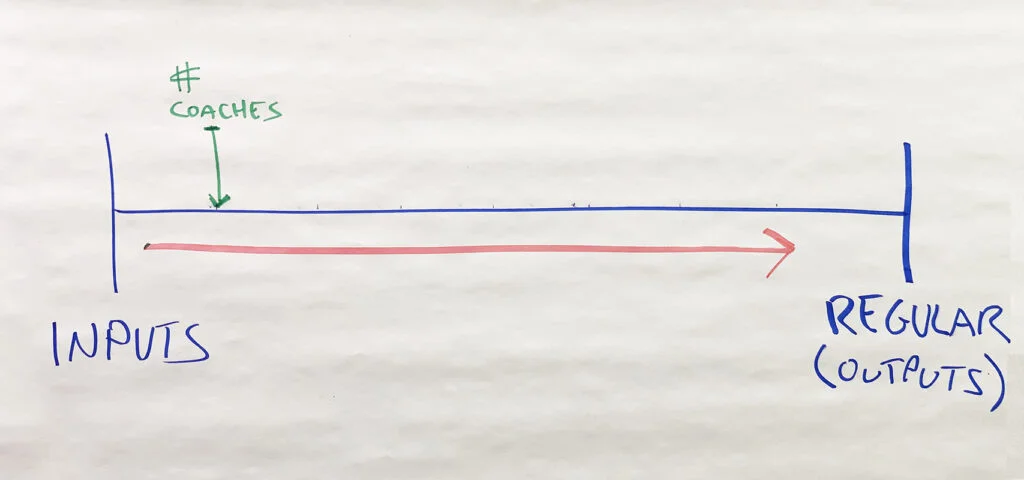

- iCoach. Of all the roles mentioned in this list, the iCoach is our favorite and thus the type of role on which we spend most time and energy. (Click here to be notified when we post our 2-part series on Building a Robust Coach Community) According to our approach, a strong network/community of coaches can be the mainstay of an innovation drive. We train coaches for three main tasks:

- Lead what we call “mini sessions”, in which 3-5 participants spend 2-3 hours solving a problem or exploring opportunities for change, as the coach facilitates using thinking tools;

- Engage in what we like to call “Opportunistic Innovation”, which means unofficially injecting innovative thinking into meetings, especially when thinking is stuck in a rut, but without declaring that it is what they are doing;

- Become the go-to person for their immediate surroundings for all matters concerning innovation.

- iCoach’s manager. The only role in the list for which one is not officially appointed, but finds him or herself in by dint of someone else’s official appointment. We will come back to the topic of coaches and their performance in more detail in a specific post, but here I will just mention that our experience shows that the most crucial factor in determining a coach’s level of engagement and their productivity is the type of support or lack thereof that they receive from their direct boss. This is why we currently include activities with coaches’ managers as a standard component in our coach training programs.

- Participant/User. Without bestowing upon them an official title, reaching these guys and gals is a huge part of the goal of the entire endeavor. Companies can create innovative ideas and offerings through the efforts of small, isolated and dedicated teams, but those that wish to achieve true transformation and cultural change, will need, by definition, to reach the rank and file of the organization. In the optimal scenario, innovation skills and behaviors cascade throughout the organization through myriad activities led by all the roles listed in our table, but these activities achieve traction only through active participation of the other associates. For example, in an organization with 100,000 employees there can be 5-10 executives in key innovation-related positions, several dozen part- or full-time innovation managers throughout areas and geographies, some 1000+ coaches, and a long-term effort to reach out to the rest of the 98,000+ employees, without which the innovation impact will be limited.

- iCoordinator. It is difficult to overestimate the importance of this role (and yet it is so often underestimated) for the success of an innovation program or drive. While other, more glamorous roles, will define strategy and put it into action, someone needs to make sure that communication flows, dates are marked on calendars, activities are monitored, action items are reported when completed and all the other small details that ensure that plans are executed. This role is usually filled by an associate with administrative abilities and an admin position, but often it is an opportunity for an admin with motivation to expand her or his horizons as the job grows and develops.

There is much more to say about these roles, as well as those not detailed here, but I believe that these notes can serve as a good basis for a discussion and analysis of what you may already have in your organization and what you wish to define going forward. As usual, you are very welcome to share your thoughts, questions, suggestions and experience either as a comment to this post, or directly to me. Any inputs will enhance our knowledge and hopefully, through our work and writing, enrich others as well.

First

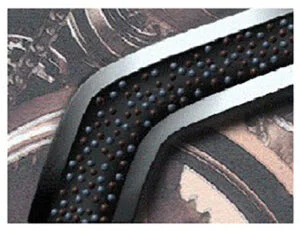

First  The problem – An engineer working at a metal processing factory encounters a problem. Hard metal pellets, used for processing metal sheets, are accelerated by an air jet in a bent pipe. The systems works continuously and the pellets abrade the pipe at the bend or “elbow”. As a result the bend must be replaced every four weeks. An attempt to install a tougher elbow did improve the situation but as the elbow had to be replaced every seven weeks, the solution was deemed unsatisfactory.

The problem – An engineer working at a metal processing factory encounters a problem. Hard metal pellets, used for processing metal sheets, are accelerated by an air jet in a bent pipe. The systems works continuously and the pellets abrade the pipe at the bend or “elbow”. As a result the bend must be replaced every four weeks. An attempt to install a tougher elbow did improve the situation but as the elbow had to be replaced every seven weeks, the solution was deemed unsatisfactory.

1. Structural – The tendency to view products and systems as a complete gestalt. Many SIT’s tools help break this particular fixedness to achieve sustainable innovation. For instance, a water saving toilet was developed by Villeroy-Boch in an SIT workshop. Multiplying the water streams resulted in more pressure in each stream, therefore requiring less water. This product won the ISH Innovation Prize and was chosen by Deutsche Bank in its transformation of its HQ to become one of the most environmentally friendly high-rises in Europe.

1. Structural – The tendency to view products and systems as a complete gestalt. Many SIT’s tools help break this particular fixedness to achieve sustainable innovation. For instance, a water saving toilet was developed by Villeroy-Boch in an SIT workshop. Multiplying the water streams resulted in more pressure in each stream, therefore requiring less water. This product won the ISH Innovation Prize and was chosen by Deutsche Bank in its transformation of its HQ to become one of the most environmentally friendly high-rises in Europe.