We’ve written plenty and posted some in the past about common myths and misapprehensions around innovation. “Not again!”, you say to yourself. For what’s more annoying than some self-important consultant(s) telling everyone how wrong they are. True. On the other hand, as we work in multiple organizations, we just see, and commit(!), so many mistakes that it seems a pity not to share what we’ve experienced, in the hopes of saving this learning-the-hard-way from as many of you as possible. But will reading through lists of mistakes really save one from repeating them? To a certain extent this is so, as alluded to in the famous saying by George Santanaya: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”. But note that, logically speaking, even if Santanaya was right, this doesn’t necessarily imply that those who do remember the past are immune from repeating it. As anyone who has raised a child will readily attest, some mistakes need to be committed and experienced in the flesh so that one can learn from them. Still, it is my belief that even if you are destined to step with eyes wide open into some traps anyway, being forewarned will help you pay a lower price, learn from the event, and maybe even adjust your course in real time. That is is why we will continue to share with you, from time to time, small collections of mistakes that we witness during our work with organizations.

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”.

This time we will focus on two misconceptions that have to do with the way those in charge of launching an innovation initiative assess their colleagues – their target audience, when designing an innovation program and its execution. Both can be seen as blind spots leading to an exclusive, rather than inclusive approach, often with dire consequences, but both can be overcome with awareness and care, perhaps aided by these practical conclusions and recommendations:

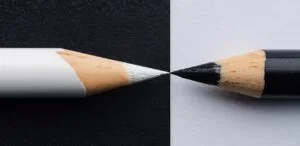

1. Black/White Vision:

Champions of innovation (and their consultants) often tend to perceive their colleagues through a divisive lens: the cool, positive, usually younger allies-in-innovation, versus the stubborn, probably older, laggards who are getting in the way of innovation with their “resistance”. As is the case with other stereotypes, this one, too, has some obvious basis in reality. But more often than not, those who “resist innovation” are, in their exasperating way, performing one of several useful roles:

- They may be pointing out to important aspects that should be maintained and safeguarded when the change-tsunami sweeps through the organization;

- They may be faithfully representing a voice of the customer, who might also find it challenging to adapt to some changes;

- They can inadvertently play the role of the proverbial canary in the mine, thus pointing out flaws in your innovation initiative or sensitive areas where you should pay more attention;

- In many cases they are simply right in their resistance to a specific change, either because in this specific case it makes more sense to maintain the status quo or because it would be wiser to keep searching for a better alternative.

Given these not-so-improbable possibilities, here are a few recommendations:

a. Listen. Listen, listen. Not fake listening, just to give the laggards the feeling that they are being heard, but sincerely consider the possibility that they may be saving you from yourself. Even if their true motivation is fear of change, they may still be right.

b. Don’t assume that veterans and older associates will necessarily be harder to convert or less able to contribute to an innovation initiative. On the contrary, they will often be its anchors, supplying the knowledge and experience to make it work. (Disclosure: the youngster writing this post has chugged by his 60th anniversary a few months ago.)

c. Don’t waste energies convincing recalcitrant managers or units. Learn from them what you can, invite them to join, and if they are still resistant, give them the time and space to join in at their own pace. Time may not yet be ripe for them, or they may be adopting a cautious strategy of first making sure that what you are offering actually works. In the worst case, they will jump on the bandwagon when it reaches cruising altitude (sorry, mixing a few metaphors here).

2. Disregarding the Middle:

To the perennial debate whether an innovation initiative is best conducted top-down or bottom-up I offer two responses, both frustrating:

- Both are necessary, to such an extent that you will probably fail unless your plan integrates both approaches. I’ve personally seen each of the two approaches being carried out disregarding the other, always with dismal results. The more common mistake in my experience is the exclusively top-down execution, whereby most of the energy and attention of a corporate unit and its external providers is dedicated to pleasing top management and enlisting their support as expressed in bombastic declarations and budget approvals. I, personally, have tended to err more in the opposite direction, advocating for a predominantly bottom-up course of action, and found to my disappointment, that even though you can achieve wonderful results by empowering the rank and file, if you fail to align with and receive substantial support from top management the entire initiative will sooner or later run out of steam, probably sooner. A combined bi-directional effort is a necessary condition for success. I recommend this as a non-negotiable condition, even if it results in a more complex, and costly, program.

- The combination of TD and BU, although a necessary condition, is not sufficient. In a typical corporation, or large organization of any kind, it is a third layer, middle management, the company’s backbone, that determines the success of an innovation initiative. Imagine a Marketing/Business/Product Director, say, in an FMCG multinational. Her team is all fired up about an upcoming innovation training, the President of the company is being interviewed in Forbes as an inspiring example of a leader who understands that “now, more than ever, the only constant is change”. So, she is sandwiched between both a BU and a TD innovation-promoting buzz. But while all this exciting discourse is buzzing around her from below and above, who will guarantee that her business unit hits the numbers this quarter? And where will the extra head count come from, if she is made to send her people to yet another course and waste others’ time on innovation forums and conferences? And, as the President halks those futuristic, exciting G3 products that will (hopefully) hit the market in 2024, after sucking up the entire R&D budget, who will fund the tweaks and adaptations that clients are clamoring for in their G2 product orders, without which there is no chance to sell the 500 million USD of the much maligned (in comparison with glorious G3) G2 wares? Middle managers, for the most part, are smart and savvy: they will figure out myriad ways to maintain the balancing act of subtly subduing their reports’ innovation-energies while posing to their superiors as innovation champions, all this whilst squeezing out the business results that everyone’s bonuses depend on. Middle managers are therefore the killers of most innovation initiatives, unless, that is, they are tasked with leading them.

To sum up this post’s message about an innovation leader’s two blind spots: no, all those old timers and other innovation-resisters are not your enemy, they should be listened to attentively and brought on board gradually according to their respective timelines and needs, and yes, you do need a Bottom-Up approach and you must combine it with serious Top-Down support, but the mix will only work if your innovation initiative is built around and under the responsibility of your organization’s backbone, its middle management.